Fangirl Culture & The Aesthetics of Admiration

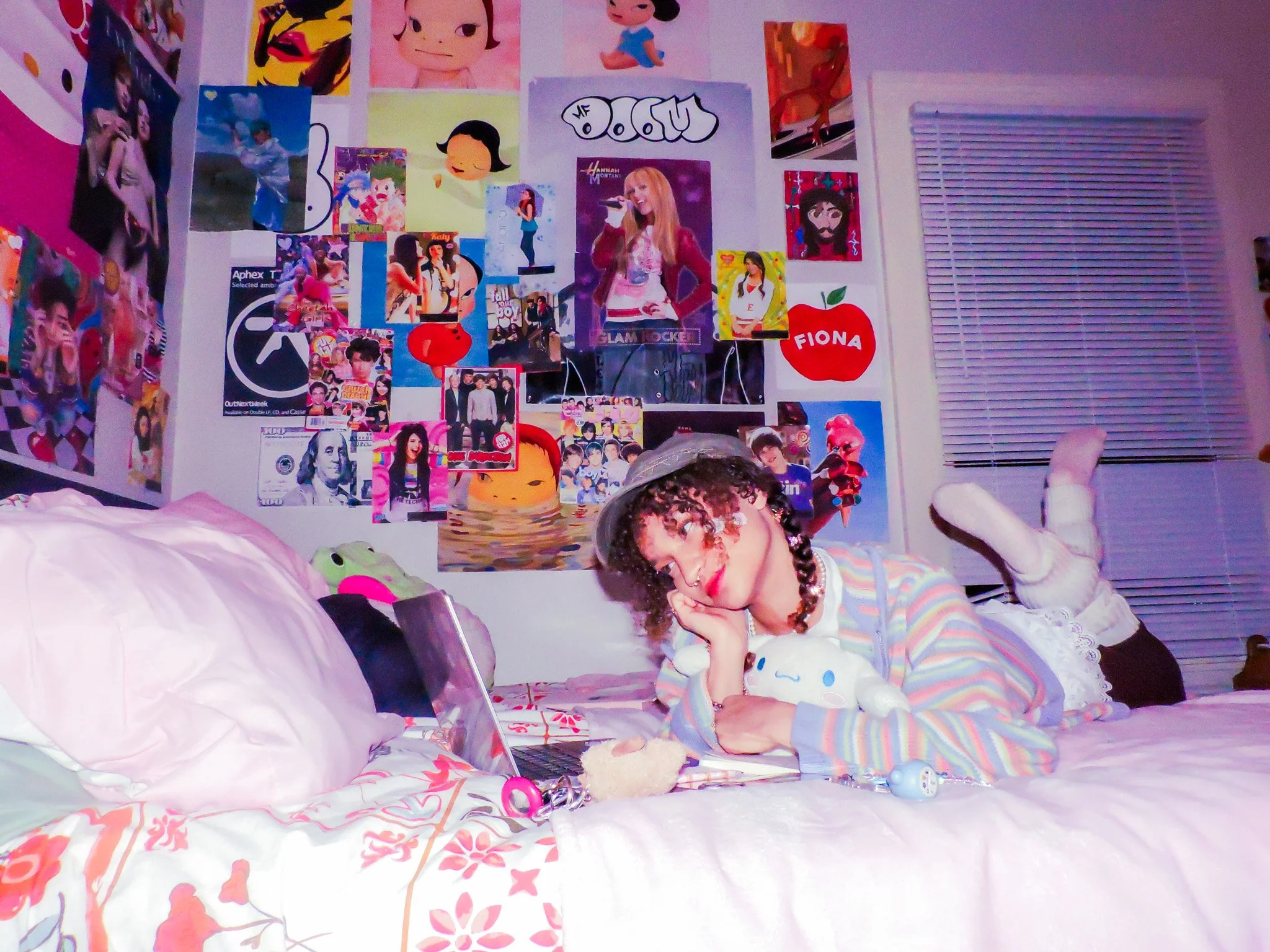

Written & Shot by: Alexis Loftis

Modeled by: Zoe Malega

The year is 2008. We see emerging artists such as Lady Gaga, Lana Del Rey, Katy Perry, Adele, and Charli XCX release their debut albums. The song “Low” by Flo-Rida ft. T-Pain is at the top of the charts. However, that couldn't have mattered less to me. My eyes were glued to the TV, watching “High School Musical" for the first time. I vividly remember sitting on the floor in front of the box TV in my living room, watching the first and second movie back to back.. My mother then took me to see my first movie in theaters, “High School Musical 3: Graduation”. Honestly, I’d say that my first love was this series. One watch through of both movies, and I was obsessed — I desperately needed to see the third in theaters. The DVDs, the soundtracks, the merch, I had everything. I remember even wearing a locket for about a year straight that had a picture of Chad from HSM in it. But my obsession, of course, did not stop with HSM. In no particular order, there was “The Cheetah Girls”, “iCarly”, Justin Bieber, One Direction, and Anime, just to name a few off the very long list. I was a self-proclaimed “fangirl” before getting my first cell phone or even hearing the word in a sentence.

The term fangirl is often followed by a certain imagery. More than likely, we think of a preteen to teenage girl with braces, glasses, and a One Direction T-shirt. She's likely crying as well, since Zayn just left the band, even though he doesn’t know she exists. It's a fairly accurate comparison, I would say, but that's more of an oversimplification. A fangirl can be described as, “a girl or woman who is an extremely or overly enthusiastic fan of someone or something.” Yet, when looking up the definition for the word “fan,” the wording is vastly different. Merriam-Webster’s definition states that a fan is “an enthusiastic devotee (as of a sport or a performing art), usually as the spectator.” So metaphorically, is the man who has multiple jerseys representing his favorite team, never misses a game, has seen them play in person multiple times, knows every player’s full name, and argues over them being the greatest team of all time a fangirl, or is he just a fan?

This double standard of the two words is referred to as a “lexical asymmetric,” which is when language assigns unequal value to identical behaviors depending on who is acting on them. The term “fangirl” is overall a gendered insult. It reveals the very fact that when women outwardly and proudly express admiration, it's seen as embarrassing, unserious, or dramatic. While men can display the same amount of allegiance to sports, video games, or anything at all, it's seen as loyalty. A man's passion is seen as character, while a woman's passion is seen as a joke. Still, these crazy, obsessed “fangirls” are the ones putting money in these companies' pockets. These fans are the consumers, and the entertainment industry depends on their loyalty.

Superficial is also a common word I see associated with being a fangirl. However, if all they cared about was looks, fangirls wouldn't have built the hidden foundation of the modern internet and social media today. Tumblr, Twitter, and Instagram were not just social media platforms. They were free online lessons on social media marketing, advertising, writing, and graphic design. Fangirls were the original social media managers long before the title existed. Growing up on these platforms really sharpened my creative eye in ways I didn't realize at the time. I learned how to use photo-editing software before I learned how to drive, and I was building moodboards long before they were a part of a syllabus. These fangirls are self-taught businesswomen and creatives. They have had these skills long before they started showing up on job applications. They are tracking trends and running data analyses from their stan accounts before they graduated high school, yet we still call them unserious? What some just consider ‘posting about hot boys’ is actually content management. These girls log, splice, and clip interviews, memes, outfits, and upcoming events tied to their favorite artists. That kind of work takes not only dedication but also an awareness of engagement, timing, and curation of your platform to stay up to date. These spaces created early communities online with like-minded creative people, all teaching and sharing information with each other. They simultaneously were fans and social media coordinators. Frankly, some fan accounts would make a case for being an overall brand.

No fandom demonstrated that power more clearly than One Direction’s. The five young men were formed on The X-Factor and rose to stardom in the early 2010s almost immediately, becoming global sensations and one of the most popular boy bands of all time. Directioners did not operate casually. These girls weren’t just listening to the music; they were creating. Monitoring album drops, making edits, watching livestreams, documenting fan wars, and sharing inside jokes within a culturally powerful online community. Despite their impact, the narrative remained the same: these girls were dismissed as weird or crazy, and the media failed to recognize their ability to build massive, self-made platforms. This devotion appeared earlier with Justin Bieber’s rise in the mid-2000s, when “Bieber Fever” became code for loyal fans whose influence dominated malls, radio, and sold-out shows. As a Belieber and Directioner myself, I had the posters, merch, and albums, and even memorized their birthdays. Social media let me grow up alongside them, making them feel tangible. They were kids just like me.

Fangirl, although a modern term, is not a new thing. This is where the Beatlemania parallel is undeniable. These young female fans of The Beatles were described the same way we see them described today: irrational, crazy, and parasocial. The media described this reaction as unusual, yet today we see how big the impact of The Beatles really was. Their career is referred to as a turning point in music and pop culture. It was one of the first times in history that women were unapologetically themselves. They collectively all saw themselves in the music.

You see a pattern in how fandoms operate, no matter the time and how people react to it. Girls love something collectively, and society demeans their interests. For it to inevitably be seen as a transformative part of history years later. Elvis was corrupting the youth. The Beatles were seen as a danger due to their large ‘out of control’ fan base. Justin Bieber and One Direction were seen as disposable and unserious. Despite this, all of these artists reshaped the industry. They left a lasting impact on the youth’s identity and what it meant to be a fan. We see that the only constant is the disrespect of the women who powered these large cultural shifts. Being a fangirl is not acceptable until it becomes a part of history. Being loud or obnoxious is not the problem; society has an issue with passionate women. When women love something on a large scale, something more than a fandom happens. They make cultural shifts.

Nonetheless, sometimes when admiration reaches beyond the music, beyond the crowd, and settles into a person's life, it can change how people form attachments with the celebrities whom they are fans of, in both a good and bad way. The word “stan,” which is slang for “stalker fan,” comes from an Eminem song,titled “The Same.” The song is based on a true story about a crazy fan whose parasocial attachments became dangerous. Although in the last couple of years, Twitter has reclaimed the word as a badge of honor, using the word “stan” positively, some even referring to themselves as “stans.” Calling yourself a stan feels heavier than the word fangirl. Stans represent the full emotional investment and participation of a specific community. You aren't just consuming content. You are fully inhabiting the lifestyle.

At its best, these parasocial relationships can be emotionally regulating. It can give one comfort in a digital space where we are only becoming lonelier. Celebrities can become emotional anchors for those struggling.On the contrary, parasocial relationships can become dangerous when admiration turns into entitlement and fans begin to believe they truly know, or are owed access to the artist. As social media blurs boundaries, devotion can escalate into fixation or surveillance. Which is a concern many artists like Chappell Roan and Doja Cat have openly addressed; stressing that accessibility is not ownership. While most fans are not harmful, the extreme end of this dynamic is tragically exemplified by John Lennon’s murder during Beatlemania. Reminding us that when artists are treated as symbols rather than people, fan devotion can become perilous.

When emotional attachment reaches a level of hyperfixation, it often reorganizes itself into overconsumption, into something economic, into a business. Therefore, it's impossible to ignore fan culture's part in the mass commodification of K-POP. This genre of music has gained global traction. Fans across the world are translating the group's content in multiple languages, making it accessible worldwide. K-POP fans are borderline marketing teams for these groups, and they are doing it for free. Streaming parties for music video drops, voting campaigns for award shows, and purchasing strategies for album drops, all of this just to ensure their favorite groups are dominating the charts and sweeping out the competition. What looks like excitement is often an organized system of fangirl labor that doesn’t just move charts, but shifts economies. K-pop, South Korea’s dominant cultural export, contributes billions annually to the country’s GDP and drives massive global media exposure. K-POP fans aren't just streaming songs. They are learning the language, visiting the country, buying Korean skincare, as well as fashion, and overall marketing Korean culture worldwide. What was once confined to our bedroom walls is now reshaping international trade.

We see more of the blatant power of the industry's overconsumption problem with the oversaturation of photocard collecting. Photocards, which are photos of artists on cardstock that come with the group's albums, are currency within these fandoms. K-POP albums are marketed most of the time with multiple versions, not for sound quality or a deluxe version, but for exclusive items. Meaning you get different photocards, stickers, or posters with each version you purchase. Corporations do this because they know the psychology of these fangirls. Many have emotional attachments to certain members and will buy multiple versions at a chance to get that rare card for novelty and the dopamine hit, putting more money in their pockets. I, at one point, was a K-POP fan and would scroll on Twitter to see the photocard leaks for the new albums. You could immediately tell which ones were going to skyrocket in price. It was like a game. Prices of photocards inflated so significantly, due to rarity or appeal. Fans trade, sell, and auction these photocards online. One of these small pieces of cardstock can sell for hundreds of dollars. The object's value is made up collectively by these fandoms, even though they are cheaply produced. Loving and listening to the artist's music is not enough. Overconsumption has now become supporting. Fandoms nowadays almost feels like it has an entry fee; to belong, you need to display, compete, and buy.

What makes fandoms so profitable is that it's not just selling products, but it also gives us a sense of belonging. Studies conducted on parasocial relationships and media addiction have shown that when a person is emotionally invested in a specific figure, real or not, it can activate the same neural pathways in your brain that a real-life connection can. This is why being a part of a fandom can feel fun and also regulating. Dopamine is impacting your reward systems and anticipation, making the wait for the drop of a new album or tour even more exciting. These studies can also reveal why, sometimes, being a fangirl can feel like an addiction. The effect of oxytocin on the brain brings a sense of bonding when engaging with something you are a fan of. For example, your favorite music artist can provide a certain positive energy in times of isolation or chaos, which can give some people a sense of stability. Our brains can't 100 percent distinguish our comfort from a favorite person we only see on a screen, versus someone we have a relationship with in real life.

Being a fangirl not only trains your brain but your perception as well. Before I was a fashion major, being a fangirl exposed me to a ton of pop culture. Being exposed to a bunch of different forms of media and deciding what I thought was the most interesting, I would argue, trained my eye for styling, narrative, composition, and branding way before I learned the full meaning of those terms. I have always been very specific about what I wear from a young age. I loved to dress up and wear fun patterns. As an adult, I have curated my closet with clothing I love, styled hundreds of people, and creatively directed many projects. I chalk up my love of visuals to my obsession with “That’s So Raven” as a child and then Tumblr in my tween and early teen years. Design was something I took into account way before I touched Adobe Illustrator. Being an OG fangirl taught me how trends circulate, how emotion can be worn, and how identity manifests in style. The older I got, the more I realized my love of fandoms influenced the way I dressed when certain trends arose. I feel like there was a moment in my fangirl career where my transparency about my interests started to shift. My previous passions didn't disappear, but my scope widened. Instead of loving one or two things intensely, the older I got, the more I opened myself up to many different forms of media. You can become a Letterboxd-loving movie buff, a ‘90s shoegaze fan, or a comic book nerd. The possibilities are endless. The more you consume many different types of media, the more your obsessions turn into appreciation. You still love art and music; You're just not memorizing their zodiac signs. Your interests are no longer consuming your identity. As the girl who once built her identity through admiration, development comes when your passions are acknowledged but not overly excessive or dominate your personality.

The fangirl does not vanish — she just evolves. She's now a marketing executive, an author, a designer, or even a photographer. Her devotion didn't vanish; it just matured. The love is still there because she has learned to enjoy herself without parasociality. Since, at the end of the day, these are just people, too. The fangirl grows up, but her joy, curiosity, and creativity never leave.